In the first few months of Donald Trump’s second term as US president, Secretary of State Marco Rubio met in-person with the heads of government of 13 of the 14 independent member states of the Caribbean Community (Caricom) bloc. Caribbean leaders were eager for such high-level diplomatic engagement with the Trump administration out of the blocks. They assessed that their respective countries’ interests—which have long rested on American support—would be served by this diplomacy.

As analysts see it, this has gone a long way toward bolstering emergent Trump 2.0 era US-Caricom relations. By meeting with Secretary Rubio, leveraging various meeting-related formats, Caribbean leaders sought to reach a meeting of the minds on the agenda for these relations, hoping to also find a modus vivendi with Washington on matters therein. The wider context: They worry about Trump’s “America First Priorities.”

Indeed, the Secretary of State playing a more hands-on role regarding US-Caricom relations has led some to believe that this is the first step toward Caricom member states’ American-focused foreign policy success in the Trump 2.0 era. However, this view misreads the state of US-Caricom relations.

Establishing just how Caribbean leaders have engaged in-person with Secretary Rubio is no less important than delving into the aforesaid misreading.

In what follows, I do so in turn.

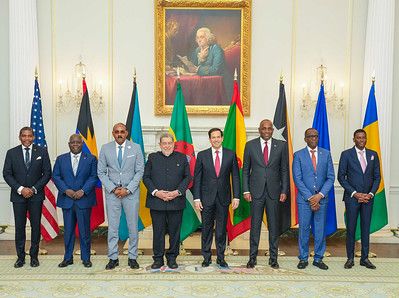

Seven Caribbean leaders met with Secretary Rubio in Washington on May 6, with an eye to advancing “cooperation in support of regional security and economic stability.” Indications are that, framed by Secretary Rubio’s blandishments about US-Caricom relations, the respective parties had a wide-ranging dialogue. At a moment of mounting American foreign policy pressure on Caricom member states, whose economic and security interests lie with the United States, those deliberations were decidedly “frank.”

This is their latest, high-profile diplomatic contact with the administration of US President Donald Trump, whose top diplomat took the opportunity to reaffirm Trump’s “America First” foreign policy positions.

This time around, Rubio—supported by some other leading Cabinet-level players and executive branch-based senior officials—hosted the prime ministers of six eastern Caribbean countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines.

They are member states of the Caricom regional grouping, as is The Bahamas. The prime minister of The Bahamas, whose country is in close proximity to the US state of Florida, was also part of this heads of government-level Caribbean delegation that met with Rubio.

In March, on the occasion of his two-day visit to three Caricom member states, Rubio met in-person with six other Caribbean leaders.

Such high-level engagements are supposed to lend themselves to “strengthen(ed) diplomatic relations.” This is in a context where one of the top foreign policy goals of Caricom member states is to build on this type of diplomatic dialogue.

Shortly following the start of Trump’s second term as US president, leaders of the 14 independent Caricom member states took the initiative to proactively engage with his administration.

This bloc of small states did so in good faith in hopes of getting their Trump 2.0 era relations with the United States on a strong footing, knowing what is at stake if all is not well with that dimension of its international relations. The reality is that these countries’ long-standing bilateral relations with the United States are a linchpin of their foreign policies. Put simply, chief among their respective foreign relations is the United States.

Caricom’s relations with the US are crucial, and even more pressing is its relationship with Trump 2.0 era Washington.

Just over three months into Trump’s second presidential term, though, US-Caricom relations are facing an uncertain moment. Growing policy differences between the two sides are testing the limits of these relations, with Washington wagering it can strong-arm America’s so-called “third border”—the Caribbean—to meet the various demands of the Trump 2.0 era.

In time, with Washington’s sights set on continuously pushing the envelope of the Trumpian notion of US interests vis-à-vis the need to demonstrate foreign policy strength, such hard-line demands and their sharp rhetoric may well grow—all the more so because of zero-sum-focused policymaking.

Accordingly, Caricom member states would have to expend more effort on diplomacy. But now, in deciding on such a course, a rethink of their approach is in order. Doing so would be a foreign policy imperative, considering that—as they take their course—Trump 2.0 era US-Caricom relations are informed by a dual narrative.

From all outward appearances, such relations have a strong base to build on. Yet the fact is that—in the foreign policy cognoscenti’s telling, behind closed doors—there is a larger truth about these relations. In practical terms, against the backdrop of broader Caricom concern about contemporary “global crises,” the said relations have lurched into a dauntingly fraught moment.

My latest published research, titled ‘US, Caribbean Countries Seize the Foreign Policy Moment: An Analysis of the Start to Uncertain Trump 2.0 Era Relations’, expounds on this assessment. The United Nations University Institute on Comparative Regional Integration Studies published this analysis as a policy brief on April 23.

An earlier version of this article, titled What the Emergent Trump 2.0 Era Says About US-Caricom Relations, was published by online news platform Caribbean News Global on May 10.